Euripides' tragedy The

Bacchae is fundamentally predicated on the structuralist binary

human/not human: the play's tension comes from anxiety over the

borders between the two states. The anxiety comes from two main

sources: how to distinguish between the human and not-human when they

appear to be the same, and how to preserve one's own status as human.

Sunday, November 25, 2012

The essay I didn't submit

This is the essay I didn't submit for "Greek and Roman Mythology": a structuralist reading of The Bacchae.

Monday, November 5, 2012

Illustrating the Eumenides

Some of these might be NSFW, if your work is uptight about paintings involving waist-up female nudity (all in the service of Art, of course!)

Someone in my course forum said they imagined the Eumenides as "monstrously bodied women with Clint Eastwood's `Dirty Harry` face". When I thought about it, I realised I had been picturing them as Japanese onryo, with white faces, black dishevelled hair and dirty white shifts, while the Delphic priestess in the play itself says she has seen paintings of them where they look like Harpies. Some of the articles I've read say that they have blood dripping from their eyes, which is a nice touch (and quite onryo-esque), but I can't track down the source for that.

I took a look at how other people have envisioned them, and there are some really spectacular renderings.

Someone in my course forum said they imagined the Eumenides as "monstrously bodied women with Clint Eastwood's `Dirty Harry` face". When I thought about it, I realised I had been picturing them as Japanese onryo, with white faces, black dishevelled hair and dirty white shifts, while the Delphic priestess in the play itself says she has seen paintings of them where they look like Harpies. Some of the articles I've read say that they have blood dripping from their eyes, which is a nice touch (and quite onryo-esque), but I can't track down the source for that.

I took a look at how other people have envisioned them, and there are some really spectacular renderings.

Thursday, September 27, 2012

You Can't Go Home Again: Exile, duality and disgust in The Island of Doctor Moreau and The Left Hand of Darkness (updated)

In Gulliver's Travels, Gulliver, after being stranded on an island with the refined Houynhnhnms and the vulgar Yahoos, returns home and is repulsed by his countrymen's similarity to Yahoos (1). Prendick and Genly experience similar feelings when meeting their compatriots again after a period of exile. Both travellers are exposed to a situation which both heightens their awareness of a fundamental binary opposition, and erodes their confidence in the border between the opposing states.

In The Island of Doctor Moreau the binary opposition is humanity versus animality. Prendrick is forced to confront the nature of this dyad, and determine how each side is constituted. His confidence in the border between the two states is eroded by his experiences with the Beast-Men. When he returns to England, he is repulsed by the animality he sees in humans (2).

In The Island of Doctor Moreau the binary opposition is humanity versus animality. Prendrick is forced to confront the nature of this dyad, and determine how each side is constituted. His confidence in the border between the two states is eroded by his experiences with the Beast-Men. When he returns to England, he is repulsed by the animality he sees in humans (2).

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Poe: the first proponent of body horror? (part one)

Body horror is defined by the ever-useful Wikipedia as "horror fiction in which the horror is principally derived from the graphic destruction or degeneration of the body. Such works may deal with disease, decay, parasitism, mutilation, or mutation." It's a term primarily associated with film: David Cronenberg is usually identified as the leader in the field, along with Clive Barker and a few other inferior directors. I think there's a very good case to be made for the Silent Hill video game series as a leading light too, as it revolves around the notion of a space where people's darkest fears and guilts are made literal flesh. The 'otherworld' of the canonical Silent Hill games is an intersection of open, bleeding flesh and rusty metal; the creatures are all human/monster hybrids or gigantic fleshy masses. But more on that in another post: I get carried away when I talk about Silent Hill.

There are definitely elements of body horror in Gothic fiction, which often fetishises the dead body as a location of intense emotions (fear, horror and disgust, but also love, romantic and erotic). It's brought to a pinnacle with the work of Poe, who might as well have taken the Wiki description of body horror as a personal artistic manifesto. I want to look at some of the devices of body horror (the Wiki definition is as good a place as any to start) and how Poe makes use of them.

There are definitely elements of body horror in Gothic fiction, which often fetishises the dead body as a location of intense emotions (fear, horror and disgust, but also love, romantic and erotic). It's brought to a pinnacle with the work of Poe, who might as well have taken the Wiki description of body horror as a personal artistic manifesto. I want to look at some of the devices of body horror (the Wiki definition is as good a place as any to start) and how Poe makes use of them.

Bradbury's bizarre love triangle: Ylla, Yll, York and the battle for the colonised space

Colonised countries are often "feminised" in the culture of the coloniser: for instance, Orientalist art of the Victorian era concentrated almost exclusively on harems and odalisques, presenting the Middle East as languorous, exotic and sexual (1). In the second chapter of The Martian Chronicles, Bradbury underlines this connection by making his female Martian Ylla represent her planet in the process of colonisation. The battle over possession of the planet is replaced with a battle over the female body.

The connection is heightened by the language used to describe Ylla. She is depicted by reference to natural images: eating fruit, handling dust, walking through mist. Mars and Ylla are described in the same language: Mars is "warm and motionless", echoing Ylla's languidity (2). They are both painted in brown, red and yellow tones.

The connection is heightened by the language used to describe Ylla. She is depicted by reference to natural images: eating fruit, handling dust, walking through mist. Mars and Ylla are described in the same language: Mars is "warm and motionless", echoing Ylla's languidity (2). They are both painted in brown, red and yellow tones.

Monday, September 17, 2012

Dejah vu: John Carter as a coloniser of two worlds

A Princess of Mars is foremost a novel about colonisation. Barsoom doubles Arizona: they have a similar desert terrain, and both are inhabited by warriors who, the book seems to say, it is the white man's destiny to rule. The same words describe the Tharks as the Apaches: they are "vicious" (1), "cunning" (2), "ferocious" (3). The connection is made explicit: "I could not disassociate these people... from those [Apache] warriors" (4).

The scene where Tal Hajus threatens to rape Dejah Thoris plays on the vicious stereotype of the non-white "brute" obsessed with despoiling white women (5). The connection between Tharks and Apaches is, again, made explicit: rather than have Dejah assaulted by Ptormel, "better that we save friendly bullets for ourselves at the last moment, as did those brave frontier women of my lost land, who took their own lives rather than fall into the hands of the Indian braves" (6).

The scene where Tal Hajus threatens to rape Dejah Thoris plays on the vicious stereotype of the non-white "brute" obsessed with despoiling white women (5). The connection between Tharks and Apaches is, again, made explicit: rather than have Dejah assaulted by Ptormel, "better that we save friendly bullets for ourselves at the last moment, as did those brave frontier women of my lost land, who took their own lives rather than fall into the hands of the Indian braves" (6).

Thursday, September 6, 2012

"Learn the Law. Say the words": Discourse and exclusion in The Island of Dr Moreau

The

term discourse is here defined as the shared language of a society. In

Foucault’s "Discourse on Language", three methods for controlling

discourse are defined which operate around the principle of

exclusion: first, objects (what can be spoken of);

second, ritual (how and where we can speak); and third, privilege

(who has the right to speak) (1). In The Island of Dr Moreau, Wells

demonstrates how, through these methods, discourse is a powerful tool for controlling and

constructing social identity.

By

defining certain subjects as forbidden, discourse functions to

control thought. If certain concepts cannot be spoken about, they can

be removed entirely from consciousness. Moreau

forbids Prendick from speaking about the possibility of injury or

death befalling the Ones with the Whips, because they cannot allow

the Beast-Men to conceive of the idea. By speaking about it,

it becomes a possibility; unspoken, it cannot exist.

Sunday, September 2, 2012

Illustrating Burroughs

For the first time in one of these posts, I'm running into the problem that a lot of the illustrations I'd like to feature are...ahem... somewhat graphic. There is a plethora of attempts to illustrate Burroughs' Barsoom, but given that most of the characters run around naked or semi-naked, and the overwhelming tendency to focus on Dejah Thoris'... assets, most of them are NSFW. It's also interesting that there's a strong tendency to sexualise the Thark women (think the Na'vi in Avatar, but green and with tusks). If you're interested, you'll have to hunt them down yourselves :)

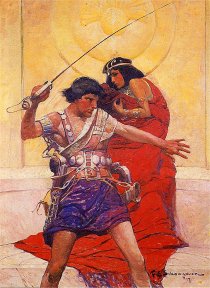

The most interesting aspect of the other illustrations is trying to decipher the visual cues to race and culture: instead of dreaming up something truly strange, many of these artists throw in visual references to some Earth culture they consider exotic. This is the classic cover, the one I've seen most often:

The most interesting aspect of the other illustrations is trying to decipher the visual cues to race and culture: instead of dreaming up something truly strange, many of these artists throw in visual references to some Earth culture they consider exotic. This is the classic cover, the one I've seen most often:

Thursday, August 30, 2012

"Perverted wisdom": Hawthorne's use of "Rapunzel" as a source for "Rappaccini's Daughter"

In "Rappaccini's Daughter", Hawthorne updates the "Rapunzel" fairytale, giving the reader an inverted, modernised version of the

story. The setting and trappings are different, but both stories convey the

same message: attempts by elders to excessively control and curtail their

children are tragic exercises doomed to failure. The name Hawthorne chooses –

Rappaccini – is the key to this reference. Rappaccini is acoustically similar

to Rapunzel, and both play on vegetable associations: rampion, rappi

(another word for rapeseed).

The character of Rappaccini is analogous to the

witch: he is first seen dressed in “scholar's black”, and black is also the

colour most associated with witches. He is also a herbalist, as were many of

the “wise women” executed as witches. This is not a fairytale, though, so Rappaccini

has the modern weapon of science rather than ancient magic in his arsenal. There's

also another version of the witch in the crone Lisabetta, who furthers

Rappaccini's experiment by conducting Giovanni through the labyrinthine

corridors to the garden. The corridors here function as an analog of the forest

through which the prince must travel to find Rapunzel.

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Poe's Moon Hoax: Too clever for its own good (Part 2)

(Continued from Part One).

Poe's Moon Hoax is not very famous. It failed as a hoax, although it succeeds as a story: mainly as a comedy, although the plot is sufficiently ingenious for an adventure yarn.

Gloriously titled "The Unparalleled Adventure of one Hans Pfaall", it's about a Rotterdam man dinged by creditors and burdened with responsibilities, who decides to take care of them both in one grand suicidal adventure. After reading up a bit on speculative astronomy and pneumatics, he constructs a balloon, complete with gunpowder-powered launching system, and rockets himself up thousands of miles into the air. He survives the launch, by the skin of his teeth (or should I say the strings of his pantaloons), but his creditors aren't so lucky.

Poe's Moon Hoax is not very famous. It failed as a hoax, although it succeeds as a story: mainly as a comedy, although the plot is sufficiently ingenious for an adventure yarn.

Gloriously titled "The Unparalleled Adventure of one Hans Pfaall", it's about a Rotterdam man dinged by creditors and burdened with responsibilities, who decides to take care of them both in one grand suicidal adventure. After reading up a bit on speculative astronomy and pneumatics, he constructs a balloon, complete with gunpowder-powered launching system, and rockets himself up thousands of miles into the air. He survives the launch, by the skin of his teeth (or should I say the strings of his pantaloons), but his creditors aren't so lucky.

Sunday, August 26, 2012

Illustrating Wells

It is very difficult to find Wells illustrations that aren't from The War of the Worlds. I find it understandable - of all his books, that's easily my favourite, and I can see why an artist would be drawn to it. There's something tremendously powerful in the images of a ravaged London and the giant metal war machines holding sway, as well as the more subtle but no less powerful images of the Red Weed, the stricken battle Thunder Child and the Artilleryman's quixotic vision of an underground civilisation.

But (to my sorrow) we're not studying War of the Worlds in my Coursera course, so I found some more relevant illustrations. We're passing out of the Golden Age of the illustrators, so many of these are from book covers or film posters.

This one has a *Boys Own Adventure* feel, which I suppose is one way of looking at the narrative:

But (to my sorrow) we're not studying War of the Worlds in my Coursera course, so I found some more relevant illustrations. We're passing out of the Golden Age of the illustrators, so many of these are from book covers or film posters.

The Island of Dr Moreau

We're moving into hard SF territory here, so the illustrations are overwhelmingly of the "pulp" variety. Some of them are nonetheless amazing: this site rounds up a few.This one has a *Boys Own Adventure* feel, which I suppose is one way of looking at the narrative:

Friday, August 24, 2012

Rappaccini's Daughter: The Hypertext Edition (work in progress)

Rappaccini's Daughter, by Nathaniel Hawthorne

We do not remember to have seen any translated specimens of the productions of M. de l'Aubepine—a fact the less to be wondered at, as his very name is unknown to many of his own countrymen as well as to the student of foreign literature. As a writer, he seems to occupy an unfortunate position between the Transcendentalists (who, under one name or another, have their share in all the current literature of the world) and the great body of pen-and-ink men who address the intellect and sympathies of the multitude. If not too refined, at all events too remote, too shadowy, and unsubstantial in his modes of development to suit the taste of the latter class, and yet too popular to satisfy the spiritual or metaphysical requisitions of the former, he must necessarily find himself without an audience, except here and there an individual or possibly an isolated clique. His writings, to do them justice, are not altogether destitute of fancy and originality; they might have won him greater reputation but for an inveterate love of allegory, which is apt to invest his plots and characters with the aspect of scenery and people in the clouds, and to steal away the human warmth out of his conceptions. His fictions are sometimes historical, sometimes of the present day, and sometimes, so far as can be discovered, have little or no reference either to time or space. In any case, he generally contents himself with a very slight embroidery of outward manners,—the faintest possible counterfeit of real life,—and endeavors to create an interest by some less obvious peculiarity of the subject. Occasionally a breath of Nature, a raindrop of pathos and tenderness, or a gleam of humor, will find its way into the midst of his fantastic imagery, and make us feel as if, after all, we were yet within the limits of our native earth. We will only add to this very cursory notice that M. de l'Aubepine's productions, if the reader chance to take them in precisely the proper point of view, may amuse a leisure hour as well as those of a brighter man; if otherwise, they can hardly fail to look excessively like nonsense.Poe's Moon Hoax: Too clever for its own good (Part 1)

Many people are familiar with the famous Moon Hoax of 1835: a series of six articles which ran in the New York Sun and purported to tell the story of some amazing lunar discoveries made by the famous (real-life) astronomer John Herschell. The articles describe an amazing variety of new lifeforms seen through a powerful telescope, including two-legged beavers and men with bat-like wings.

The Sun Moon Hoax employs a great many devices to make it seem real to the reader: it harnesses novel and relatively-incomprehensible science (astronomy) and technology (telescopes); it puts the tech in the context of well-documented prior efforts in the field, by describing in detail the history of optics and how it led to the creation of Herschell's extremely powerful telescope; it grounds the characters in the real-world by utilising Herschell and alluding multiple times to his education, awards and achievements; and it sticks in a nice "appeal to authority" by pretending to be a reprint of articles which appeared in the (real-world) Edinburgh Journal of Science and a allusion to the "forty pages of illustrative and mathematical notes" which accompanied the original.

The Sun Moon Hoax employs a great many devices to make it seem real to the reader: it harnesses novel and relatively-incomprehensible science (astronomy) and technology (telescopes); it puts the tech in the context of well-documented prior efforts in the field, by describing in detail the history of optics and how it led to the creation of Herschell's extremely powerful telescope; it grounds the characters in the real-world by utilising Herschell and alluding multiple times to his education, awards and achievements; and it sticks in a nice "appeal to authority" by pretending to be a reprint of articles which appeared in the (real-world) Edinburgh Journal of Science and a allusion to the "forty pages of illustrative and mathematical notes" which accompanied the original.

Thursday, August 23, 2012

The power of namelessness in Frankenstein

Frankenstein's monster's namelessness denotes his abject status, but - paradoxically - by not defining and curtailing him, it allows him to take control of the novel.

Namelessness can be used to dehumanise; by denying something a name, we deny it authority and individuality. It is an effective technique for imposing control or for cultural assimilation. For instance, in the American South, African slaves had their real names taken away and were re-christened by their "masters"; in many cases, these names were intended to demean them or to signify their conversion to Christianity. Victor, by refusing to give his creature a name, denies him legitimacy and de-personalises him.

Namelessness is also common among monsters. Another famous fictional creation, Grendel's mother from "Beowulf", although arguably more monstrous than her son, is defined only in relation to him. Many monsters, such as the Wolfman and Mummy, are known by their type rather than an individual signifier. Frankenstein's monster is not even given that privilege: at various times throughout the text, he is a "wretch", a "monster", a "creature", a "daemon", a "devil", a "fiend". He lacks not only a personal name, but also a categorical name, further emphasising his isolation and denoting his liminal status. By refusing to categorise him, Shelley opens him up to endless interpretations: we can see him as either a wretched Adam or a twisted Lucifer, amongst other things.

More Poe illustrations: W. Heath Robinson

I first came across W. Heath Robinson's illustrations in an old copy of The Water Babies.(I have a vague memory, too, of some pictures in a strange old book of stories - an omnibus for children, possibly a magazine annual? - including a story about Christopher Wren designing St Paul's Cathedral. It was very Victorian in tone: there were definitely some angels involved). I was surprised to find he did some illustrations for Poe as well, as Poe's macabre sensuality is pretty far removed from the kind of prim morality tale I associated with Robinson.

But Robinson's Poe illustrations are gorgeous! They're a bit crimped and stylised - his use of borders and flat 2D planes makes everything look like a stage set - but he picks up on Poe's Romanticism in a way that Beardsley and Clarke don't.

Here's a double-page illustration for "The Raven":

He's making real the dream-vision of Poe's narrator. (This is something most illustrators don't have the guts to do - Doré's rococo illustrations of the poem, which I confess I don't really like, confine themselves to depicting the narrator in his study while various visions appear to him). I love the way everything seems to swell and roll across the page, while the straight, sharp black raven slices across it. It's a more complex illustration than it first appears: the eye is drawn around and around it, and the landscape strongly suggests old Chinese scrolls. Who are the figures sensuously entwined in the foreground? Lenore and the narrator? Lenore and Death? The draperies strongly suggest a winding-sheet.

But Robinson's Poe illustrations are gorgeous! They're a bit crimped and stylised - his use of borders and flat 2D planes makes everything look like a stage set - but he picks up on Poe's Romanticism in a way that Beardsley and Clarke don't.

Here's a double-page illustration for "The Raven":

He's making real the dream-vision of Poe's narrator. (This is something most illustrators don't have the guts to do - Doré's rococo illustrations of the poem, which I confess I don't really like, confine themselves to depicting the narrator in his study while various visions appear to him). I love the way everything seems to swell and roll across the page, while the straight, sharp black raven slices across it. It's a more complex illustration than it first appears: the eye is drawn around and around it, and the landscape strongly suggests old Chinese scrolls. Who are the figures sensuously entwined in the foreground? Lenore and the narrator? Lenore and Death? The draperies strongly suggest a winding-sheet.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Ladies' night

A recent discussion on the Coursera forums started me thinking about Japanese folklore and horror movies and the concept of the monstrous feminine. We came to the conclusion in the discussion that many female monsters are dichotomous: beautiful human/hideous monster. Lamia, Sil from Species: there are many examples of this. It's true of some Japanese folklore too: there's Otsuyu from Botan Dōrō, Kuchisake-onna, Yuki-onna.

But the dominant figure of horror in Japanese cinema is for sure the onryō - the vengeful ghost. Usually she is female; definitely the most memorable examples have been. Sadako from Ringu, Katsuya from Ju-On, Mitsuku from Honogurai mizu no soko kara (Dark Water). They're not exactly beautiful, either, these ghosts: clad in costumes which take their cues from kabuki, they wear white burial shifts, dead-white faces, long black hair hanging down, and shadowed eyes. They have their origins in folklore, most famously Oiwa in Yotsuya Kaidan. Here she is:

But the dominant figure of horror in Japanese cinema is for sure the onryō - the vengeful ghost. Usually she is female; definitely the most memorable examples have been. Sadako from Ringu, Katsuya from Ju-On, Mitsuku from Honogurai mizu no soko kara (Dark Water). They're not exactly beautiful, either, these ghosts: clad in costumes which take their cues from kabuki, they wear white burial shifts, dead-white faces, long black hair hanging down, and shadowed eyes. They have their origins in folklore, most famously Oiwa in Yotsuya Kaidan. Here she is:

Illustrating Poe

Aubrey Beardsley is one of my favourite illustrators (neck-and-neck with Edward Gorey) and one of the first editions of Poe I owned was one for which he did the illustrations. And what illustrations they were! I don't think there's anyone who could have captured Poe's combination of obsessive, excessive morbidity and sensual romanticism like Beardsley.

Look at this illustration for "The Black Cat":

There's so much character there. The cat is deformed to the point where it looks more like a grotesque imp, and somehow, despite the fact that the dead woman is bright white against the black background, the cat still draws the eye and commands the picture.

Look at this illustration for "The Black Cat":

There's so much character there. The cat is deformed to the point where it looks more like a grotesque imp, and somehow, despite the fact that the dead woman is bright white against the black background, the cat still draws the eye and commands the picture.

The abject of my affections: A Kristevan take on Frankenstein

Theorist Julia Kristeva originated the idea of the "abject" - "the human reaction (horror, vomit) to a threatened breakdown in meaning caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object or between self and other" (Felluga). The best example of the abject is the corpse, as it "traumatically reminds us of our own materiality" (ibid). To sketch it in simpler strokes; in the abject we identify something which used to be human, but is no longer. We react to the abject with a mix of horror, pity and fear. Although the novel was written many years before Kristeva's theory, the monster in Shelley's Frankenstein is an excellent example of the abject.

On Hawthorne

I've always had problems reading Hawthorne: I've started The House of Seven Gables no less than seven times, but could never make it past the first chapter without falling into a doze. I'd never tackled any of his short stories before taking the Coursera "Fantasy and Science Fiction" course, and to my surprise, I'm enjoying what I'm reading. I always thought of Hawthorne as a bit stuffy and stultifying, but the stories are rich, voluptuous and risky. "Rappancini's Daughter" is my favourite so far. Hawthorne's prose is more refined and the setting is more romantic, but it reminded me a bit of Clark Ashton Smith's (much more lurid) "The Garden of Adompha". Smith has a bad case of Science Fictiony Name Syndrome going on, but it's worth it for the extreme purpleness of the prose.

A formula to think about:

Lovecraft + sex - excessive Euro-worshipping and erudition = Clark Ashton Smith.

Here's the fantastic cover illustration for "The Garden of Adompha", done in the inimitable Weird Tales style:

A formula to think about:

Lovecraft + sex - excessive Euro-worshipping and erudition = Clark Ashton Smith.

Here's the fantastic cover illustration for "The Garden of Adompha", done in the inimitable Weird Tales style:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)